The hamon is essential to a true Japanese sword. Follow along as we explore what the hamon is, how to judge its quality, its practical function, and the history behind it.

What Is Hamon?

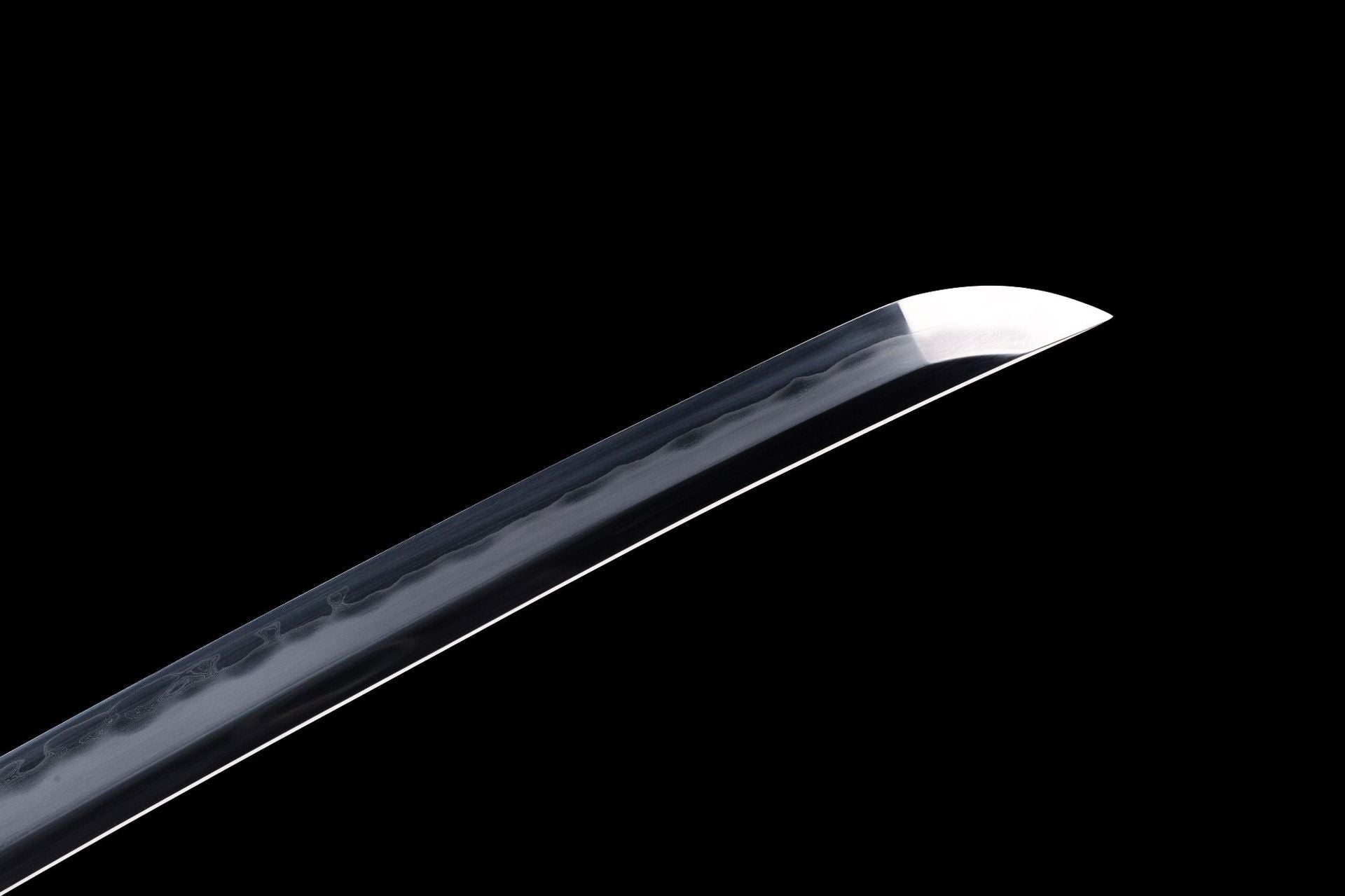

One of the defining traits of a Japanese sword is its hamon—the visually distinct band that runs along the edge after differential hardening. After forging, the smith applies a carefully patterned clay mixture (tsuchioki) to the blade, heats it, and then performs the quench (yaki-ire), traditionally in water. This process creates a hardened edge zone made primarily of martensite—a steel structure significantly harder than the body of the blade—producing a unique hamon on every sword.

Any properly forged, functional Japanese sword will show a genuine hamon created by heat treatment, not surface decoration.

What Makes a Good Hamon

Because the hamon is so important, anyone interested in nihontō (Japanese swords) should understand how to judge it. In general, a fine hamon:

- Exhibits a clear, continuous boundary—the nioiguchi or habuchi—cleanly separating the hamon from the body (ji) with no gaps or breaks, running uninterrupted from tang to tip.

- Shows crisp activity rather than a flat, simple line: complex undulations and countless small details often indicate skillful heat control and a healthy polish.

- Maintains consistent visibility along the blade. Faded, patchy, or muddy areas can suggest heavy wear, tired polish, or past over-polishing.

Keep in mind: a blade with poor condition, very old polish, or one that has been repolished many times over centuries may have a hamon that is difficult—or even impossible—to see with the naked eye.

How to View the Hamon Clearly

Even a healthy hamon can be elusive if you view it incorrectly. First, wipe the blade absolutely clean. Use a strong, steady light and adjust your viewing angle so the tip (kissaki) sits just below the brightest part of the light source. Look near the reflective band of the surface; with the angle just right, the nioiguchi—the hamon’s boundary—snaps into view.

Reading the Details: Nioiguchi, Habuchi, and Ashi

When the viewing angle is correct, the hamon reveals a wealth of detail:

- Nioiguchi (匂口) / Habuchi (刃縁): the luminous boundary line that marks the edge of the hamon. In a quality blade it runs clearly and without interruption from base to tip.

- Ashi (足): streaks or “legs” that descend from the boundary toward the cutting edge. Often nearly perpendicular to the line of the hamon, ashi can be very short and subtle or long and obvious. Their presence often indicates a good mechanical integration between the hardened edge steel and the softer body, helping resist edge chipping by distributing stress.

Why the Hamon Matters in Use

A working sword requires a hard, sharp edge. The hamon’s complex structure exists to achieve that function. Early Japanese swords (5th–6th centuries CE) were straight and carried a narrow, straight hamon composed mainly of martensite along the edge. While a fully martensitic blade is extremely sharp, it is also brittle and prone to damage in use.

To solve this, smiths constructed the blade body from tougher, more ductile structures such as pearlite and ferrite. The design philosophy of the Japanese sword is to exploit the different properties of steels in different regions of the blade, producing a weapon that is effective, durable, and resilient.

How Hamon Evolved Through History

Over centuries, swords grew larger and developed curvature, and the hamon grew wider and more intricate. Early straight hamon were simple borders: a band of hard martensite meeting softer steel along a near-straight interface, which could sometimes delaminate or chip with a hard strike.

To counter this, smiths created broader, wavy patterns—rows of semicircles or waves with changing height and width. In complex hamon, the visible boundary may climb toward the blade’s mid-width at its peaks and dip down near the edge at its troughs. Think of these waves as extending the contact length between hard and soft regions, letting them interlock like gear teeth and thereby strengthening the bond. Such patterns also help mitigate damage during use by spreading stresses more evenly.

These developments first appear on swords from the 11th–12th centuries and advanced further through the Kamakura period (1185–1333). The modern Japanese swords we admire today largely descend from Kamakura-era innovations.

Glossary of Key Terms

- Hamon (刃文)

- The visible tempered band along the cutting edge created by differential hardening during yaki-ire.

- Tsuchioki (土置き)

- The patterned application of insulating clay before hardening; it controls where the blade hardens.

- Yaki-ire (焼入れ)

- The hardening (quenching) step, traditionally in water, that forms the martensitic edge.

- Nioiguchi (匂口) / Habuchi (刃縁)

- The bright boundary line marking the edge of the hamon; it should be continuous and clear.

- Ashi (足)

- “Legs” or streaks extending from the hamon toward the cutting edge, helping arrest cracks and distribute stress.

- Martensite

- A very hard steel microstructure formed by rapid quenching; provides sharpness and wear resistance.

- Pearlite / Ferrite

- Tougher, more ductile steel structures used in the body of the blade to add resilience and prevent breakage.

- Kissaki (鋒)

- The tip of the blade; positioning it just below the light source helps the hamon “pop” into view.

Katana Hamon FAQ

Does every real katana have a hamon?

A properly forged, functional Japanese sword will display a true hamon formed by differential hardening. On very worn or heavily repolished blades, it may be faint or no longer visible.

How can I make the hamon easier to see?

Clean the blade, use a strong consistent light, and adjust the angle so the kissaki sits just below the light’s brightest point. View near the reflective band until the nioiguchi becomes distinct.

Why are some hamon straight while others are wavy?

Straight hamon are typical of early blades. Wavier, broader hamon increase the interface between hard and soft regions, improving durability and damage resistance—an evolution seen from the 11th–12th centuries and refined in the Kamakura period.

Read more

How Folding and Forging Actually Works — The Art of Shita-Kitae and Age-Kitae So, let’s say you’ve got a chunk of tamahagane, the traditional Japanese steel used to make a katana. Congrats — now th...

A katana isn’t just a sword made from one type of metal. It’s actually a carefully crafted structure made from layered and combined steel types. Inside, it has a softer iron core called shingane, w...

Shop katana

Our katana store offers a wide selection of japanese swords — from traditional katanas and anime-inspired designs to fully functional blades — featuring a variety of materials and craftsmanship to suit your preferences.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.