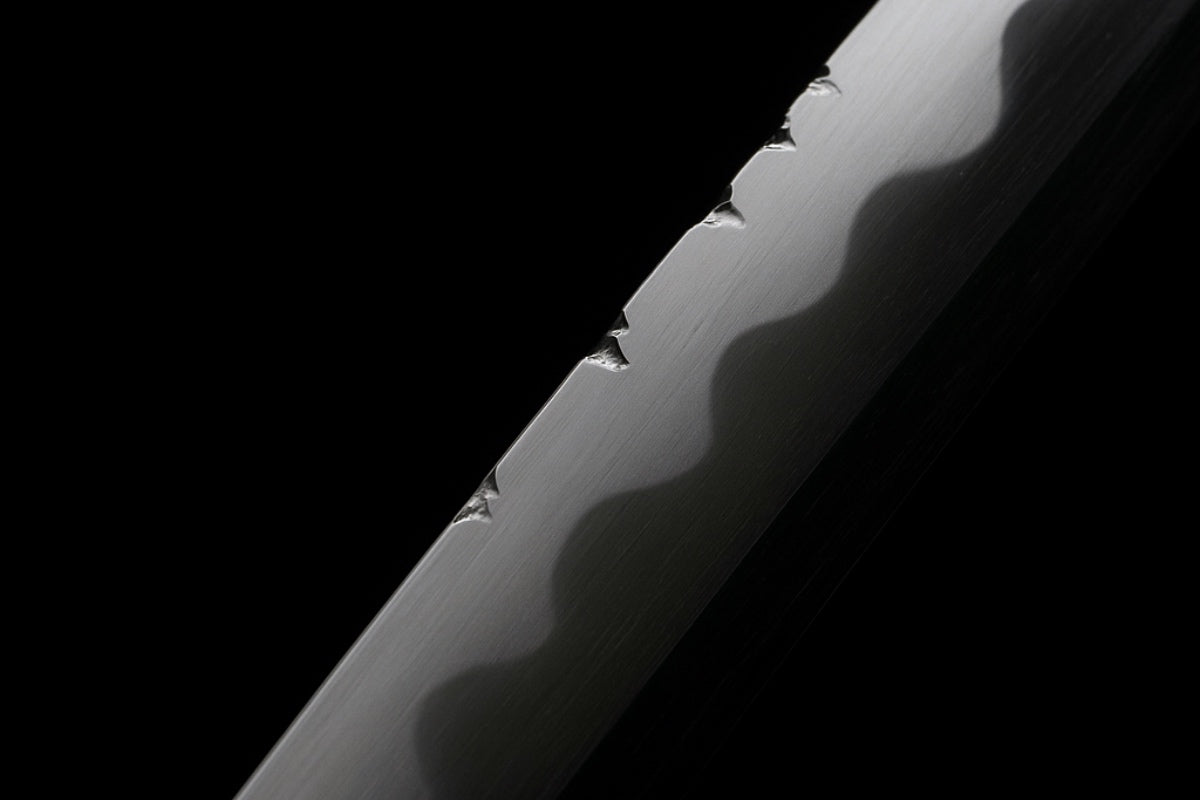

The hamon—or temper line—is one of the most visually iconic and technically important features of a Japanese sword. This crystalline boundary marks the difference in hardness between the blade edge and the spine, created through centuries-old heat treatment techniques. But beyond its function, the hamon reveals stunning natural beauty, artistry, and smithing lineage.

Table of Contents

- How the Hamon Is Formed

- Visual Phenomena Within the Hamon

- Types and Styles of Hamon Patterns

- Midare Hamon: The Chaotic Beauty

- The Boshi: Hamon at the Sword Tip

- Art, Function, and Lineage

How the Hamon Is Formed

Before quenching, swordsmiths apply a clay mixture over the sword’s body, leaving the edge bare while coating the spine. When the heated blade is plunged into water, the exposed edge cools rapidly and hardens, while the insulated spine cools slowly and remains softer. This thermal difference causes a metallurgical transformation, producing the hamon—a visual boundary between hardened martensite and softer pearlite structures.

Visual Phenomena Within the Hamon

Beyond its functional origin, the hamon offers a canvas of intricate textures: misty layers, golden threads, lightning streaks, or even crystalline dots. These are not surface effects—they run deep within the blade, resulting from extreme temperature shifts and folding patterns. Even after polishing, the same patterns re-emerge, attesting to the sword’s inner beauty.

Types and Styles of Hamon Patterns

In early sword-making, the hamon was typically straight (suguha), reflecting Chinese-style simplicity. Over time, smiths began crafting wavy lines (notare), followed by more complex, creative forms like choji (clove shapes), gunome (alternating arcs), sambon-sugi (three-cedar), and toran (storm waves).

Some resemble pine bark, whirlpools, wood grain, or even floating clouds and sunset mist. These styles are not only aesthetic choices but also signatures of specific sword schools and eras.

Midare Hamon: The Chaotic Beauty

Highly irregular and undulating hamon styles are known as midare. When viewed with the blade edge facing down, the crests of these waves are called yakigashira. Among midare forms, two prominent types dominate:

- Gunome: Rounded wave crests, known for structural reliability.

- Choji: Clove-bud shapes extending into the edge with visible "feet"—offering artistic flair but less structural function.

While gunome contributes to blade performance, choji often elevates aesthetic value. Each requires expert control over the quenching and clay application process.

The Boshi: Hamon at the Sword Tip

The hamon continues into the kissaki (tip) and is called the boshi. The shape and presence of the boshi is a key indicator of craftsmanship and blade integrity. A missing or poorly executed boshi suggests either crude forging or heavy repair—possibly due to breakage or reshaping. Without it, the tip’s hardness is questionable, severely lowering the sword’s value.

Art, Function, and Lineage

In ancient times, smiths often specialized in one or two hamon styles, forming recognizable lineages. Modern swordsmiths, however, may reproduce many styles on demand, reducing stylistic uniqueness but expanding artistic flexibility. Still, the hamon remains both a technical fingerprint and a poetic expression of Japan’s metallurgical heritage.

Note: The hamon is not just a line—it is a living trace of fire, steel, and craftsmanship. Understanding it is key to appreciating the full depth of the Japanese sword’s beauty and history.

Read more

Due to their complex forging process, exposure to battle damage, and centuries of aging, samurai swords often exhibit a variety of flaws. While minor defects that do not affect performance are usu...

Discover the tsuka, or handle, of the Japanese sword. Learn how its design, materials, and wrapping styles balance functionality, comfort, and artistic expression.

Shop katana

Our katana store offers a wide selection of japanese swords — from traditional katanas and anime-inspired designs to fully functional blades — featuring a variety of materials and craftsmanship to suit your preferences.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.